Permanent Equity’s Guide to Beer Money

Contents

These insights were adapted from Permanent Equity CIO Tim Hanson’s newsletter, Unqualified Opinions. You can find more and sign up at https://www.permanentequity.com/newsletters.

Intro

At the risk of dating ourselves, we are old enough to remember Groupon and ACSOI. ACSOI was a measure of that once publicly-listed company’s profitability if you didn’t include what it cost to acquire customers or what it paid employees in stock-based compensation. This measure, of course, conveniently ignored the fact that without customers or employees, Groupon wasn’t much of a business!

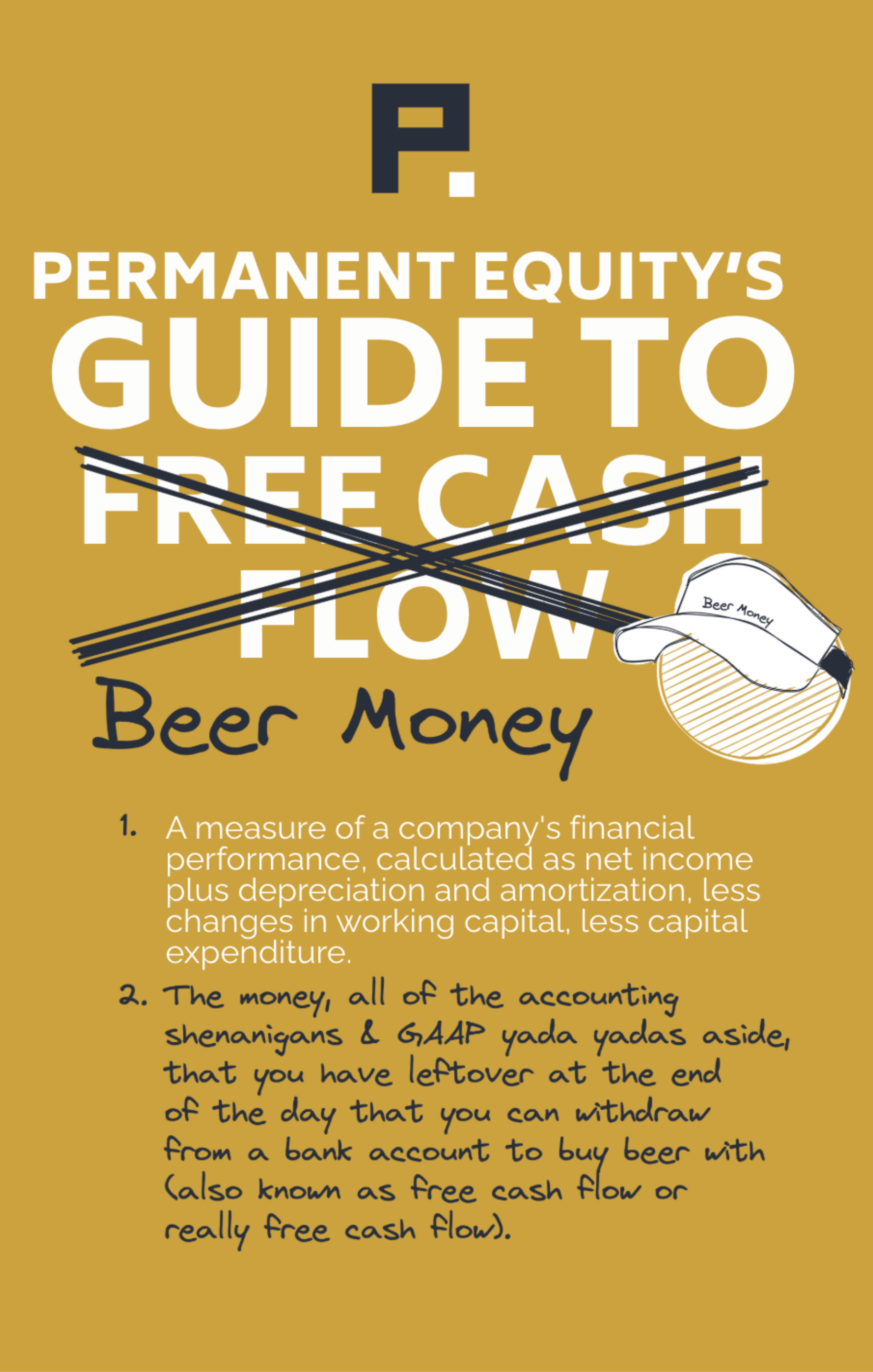

At Permanent Equity, the way we measure the value of a business is in terms of how much Beer Money it produces. Not ACSOI, not EBITDA, and certainly not Adjusted EBITDA. Because Beer Money is the money, all of the accounting shenanigans and GAAP yada yadas aside, that you have leftover at the end of the day that you can withdraw from a bank account to buy beer with.

That’s what we find the healthiest businesses produce, and we hope this guide is helpful in thinking about how to generate more of it. Cheers.

Growth, and Other People’s Money

Sometimes your investors are dangerous.

We saw the financials recently of a relatively small business that aspires to be a premium global consumer brand. Not only that, but it’s made some progress towards achieving that goal and may ultimately get there. But what was interesting was the trajectory of the company’s growth and what that might portend.

Rewind three years and this was a company that was growing ~25% annually with gross margins around 50% – well above the industry average. That’s a real success story: good growth with premium pricing. Those numbers suggest that there was a there there that’s really resonating with consumers.

At that time the company decided to take on outside capital so (1) the founder could take some chips off the table and (2) the company could invest in its balance sheet. That capital came from one of the big well-known firms through a fund that had less than 5 years left on its fund life.

What do you think happened next?

With a new investor that wanted to be out in less than 5 years, they mashed the pedal down on growth. Sales almost doubled the first year, and then doubled again. But gross margins dropped 1,200 basis points, profitability evaporated, and the business started to consume cash as inventory piled up on the balance sheet. Yes, you can achieve incredible temporary growth if you’re in-stock, slash prices, and don’t care about cash flow.

Now the investor was back out in the marketplace trying to sell its stake at a valuation of 3x sales, believing it had earned 5x on its investment in just a few years.

Are you a buyer?

Margin is one of the hardest metrics to recover in the marketplace. If you build market share on lower prices, your customer is not likely to stay with you when you raise them and raising prices is not something you can do when you have elevated levels of seasonal inventory. So what happens next is anybody’s guess.

Every company faces inflection points, and what an organization decides to do next usually depends on what that organization is optimizing for. Very often what the organization decides to optimize for ends up matching what its investors are optimizing for. And while everyone says they’re a “long-term” investor, people define that term differently. This is why one should figure that out before taking someone else’s money and choose carefully before you do.

Small But Important

The best thing to be?

If you haven’t read Capital Returns (a collection of investor letters published by London-based firm Marathon Capital between 2002 and 2015), a theme of the book is that companies that earn high returns are often ones that do a small, but important thing for their customers, making them a critical part of a project or value chain or supplier, but a small percentage of total spend.

Here are a few examples of Marathon musing on that topic:

August 2011: Another class of business whose weight in our portfolios has expanded…has been companies with annuity-like revenue streams…The common theme here is a longer-term commitment made by the customer, together with an element of inertia when it comes to renewals. These factors…make for significant barriers to entry and high and sustainable returns. This is particularly true where the cost of the service is only a small proportion of the customer’s total spending.

February 2013: Pricing power is further aided [when a component]...plays a very important role…but represents a very small proportion of the cost of materials.

May 2014: Sometimes a product is so embedded in a customer’s workflow that the risk of changing outweighs any potential cost savings…The very best economics appear…in a situation in which the cost of the product or service is low relative to its importance.

February 2015: Our preferred growth stocks undertake apparently unglamorous activities that are essential to their customers – so essential, in fact, that customers pay little attention to what they’re being charged…Here, reliability weighs more highly than price.

Similarly, one of our biggest learnings at Permanent Equity has been that when it comes to generating Beer Money, the place to be in business with your customer is small, but important (with our waterproofing and commercial fencing businesses being prime examples of this fact). Because small, but important, businesses, for all of the reasons Marathon cited, have the best of everything: pricing power, margins, cash conversion, growth opportunities, etc.

The reason is that small, but unimportant businesses are undifferentiated afterthoughts, large, but unimportant businesses are commodities, large, but important businesses are highly scrutinized, but small, but important businesses have carte blanche. And carte blanche is some place to be.

Why So Much Cash?

It’s a feature, not a bug.

One question we get quite a bit from investors when they see Permanent Equity’s track record for making cash distributions from our funds is why do you and your companies throw off so much cash? Because with the S&P 500 yielding less than 2% and many public companies paying no dividends at all, ours look high by comparison. There are a few reasons.

First, our businesses are typically structured as pass-through entities. What this means is that they don’t pay corporate income taxes, but rather “pass-through” both tax liability and the cash to pay that tax liability to their owners. In other words, the dividends paid by our companies and funds, unlike the dividends paid by C corps, are issued on a pre-tax basis, which will make them definitionally higher.

Second, when it comes to capital allocation, there are really three things a business can do with its money:

Pay dividends.

Buy back stock.

Reinvest in the business.

For C corps, they not only pay dividends after paying income taxes, but individuals receiving them then have to pay another 15% to 20% in dividend tax. Leaving aside the issue of whether this double-taxation is fair or not, what it means for C corps is that they get more bang for their buck on behalf of their owners by either buying back stock or reinvesting (because those activities are not taxed twice and reinvestment can be tax-advantaged through policies like accelerated depreciation), so if they are being rational about value creation they will do more of that and less paying of dividends.

Third, incentives. Because we like dividends (more on that below), the people who run our businesses are typically bonused based on the amount of cash they distribute out of the business. This stands in contrast to the compensation plans of many CEOs of public companies who are rewarded based on stock price appreciation. The thing about dividends is that when they are paid out, cash (a balance sheet asset) leaves the company, so the stock price goes down (not good if your bonus depends on the stock going up). Buying back stock and reinvesting, on the other hand, are both things that give a stock price a better than 0% chance to go up. “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome” indeed, as Charlie Munger used to say.

Fourth, there’s a relationship between the size of a business and its ability to tolerate reinvestment and growth, and our experience has been that the more aggressively one tries to reinvest in and grow a small business, the more risk one introduces into its operations. Because remember that anytime you create the opportunity to make gains, you are simultaneously creating the opportunity to take losses. So while our operating team works with our companies to maintain ranked lists of reinvestment opportunities, they are typically never executing on more than one or two of them at once. That’s in order to stay focused on making the reinvestment we’re making successful, but also so that, if it isn’t, we haven’t bet the company.

Fifth, cost of capital matters. When it comes to reinvestment, our businesses are typically reinvesting in scaling assets such as vehicles, machinery, or facility expansions. Because these assets are tangible and easy for a lender with a lower cost of capital such as a bank to underwrite, it’s typically cheaper to finance them that way than with retained earnings. And so we do.

Finally, the golden rule applies. As investors, since we are the ones who have to face the consequences of any losses incurred by our investment decisions, we think we should also be the ones who get to decide what to do next with any gains – and we think our investors deserve the same courtesy. This is why distributions paid by our companies to our funds are almost entirely paid forward to the fund investors as beer money rather than recycled by us into something else.

BS Earnings & Unconscious Reinvestment

Beware.

At Permanent Equity, we have aspirations that our portfolio companies generate in cash at least 90% of what they claim to have earned in a given month. Some call this free cash flow conversion, but we refer to it as earnings quality, and if any of our companies come up short of that 90% target in a given month, and we have spreadsheets to measure it, we want to understand why.

That’s because it’s in understanding why a business did or did not have good earnings quality that a lot of aha moments happen, in particular with regards to operating a small business. For example, one idea we’ve come to believe is that reinvestment, which is what is happening if earnings are not showing up on the balance sheet in cash, takes two forms: (1) conscious and (2) unconscious.

Conscious reinvestment is great. It’s the deliberate deciding on and then spending against a strategic priority whose risk/reward profile is both known and attractive. And if we have a business that’s not generating much cash because it’s consciously reinvesting, that’s, again, great. We’re using pretax dollars to drive growth and the cash should show up later.

What’s insidious, however, is unconscious reinvestment. This is what we’ve started calling it when a bunch of invoices get paid early because someone is on vacation next week, we decide to buy instead of lease some new equipment to get a price break, we hired someone a little earlier than plan because it was a serendipitous fit, and the back office got busy and missed a billing cycle or didn’t make any phone calls to inquire about past due receivables.

Because each one of those decisions on their own isn’t the end of the world, but if they all happen in the same month, and they can because different individuals are the decision-makers and they may not be coordinating, poof, our earnings quality may have just got cut in half without anyone realizing it. And God forbid if you fill that gap with a draw on a line of credit without figuring out why the gap exists in the first place.

That’s why having a goal of banking at least 90% of its earnings is effective. It doesn’t mean it will happen every month, but if it doesn’t, and you’re not consciously reinvesting, at least the shortfall will shine a light on your unconscious reinvestment and therefore on what process improvements need to be implemented in order to nuke it.

Your Husband Owes Me Money

I can wait.

One thing we’ve learned at Permanent Equity is that if you let a business sit on too much cash, that liquidity can lead to complacency, which is the enemy of performance. So we work together with our portfolio companies to set minimum cash balances that are sufficient to provide stability during dry spells, but sweep any excess cash out regularly in order to maintain focus and discipline.

One of my favorite examples of how effective this best practice can be comes from a CEO we know who operates without a line of credit and only a few months of payroll on his balance sheet. By being financially lean, he believes his managers develop a healthy paranoia around money and an appreciation for the importance of earning and collecting it. They’ve got to know their unit economics and be deliberate about collecting and paying bills. It’s only then that (and this is a true story) when it becomes clear in the course of a weekly AR meeting that a particularly difficult customer isn’t paying his bills or even picking up phone calls that the CEO himself got up from the table, drove to the customer’s home inside of a gated luxury subdivision, and knocked on the door.

That knock was answered by the customer’s wife, who was otherwise going about her business preparing dinner. But she answered the door to find someone she’d never met standing there, who said, “Hi. My name is _____. Your husband owes me money. I can wait.”

Now, this isn’t necessarily how they teach working capital management in business school, but the technique proved effective in the sense that the project manager left with a check. Because imagine being on either side of that knock.

The information, opinions, and views presented in this publication are provided solely for general informational and educational purposes. This publication is not, and should not be construed as, an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security, financial instrument, or other product. It does not form the basis of any contract and does not create a fiduciary, advisory, or client relationship with Permanent Equity Management, LLC.

The information, opinions, and views presented in this publication are provided solely for general informational and educational purposes. They are of a general nature, have not been tailored to the specific circumstances of any individual or entity, and do not constitute a comprehensive statement of the matters discussed. This material should not be interpreted or relied upon as investment, legal, tax, accounting, regulatory, or other professional advice, and nothing in this publication is intended to be or should be construed as such. You should obtain advice from your own professional advisors regarding the applicability of the information to your particular circumstances.

The views and analyses expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent or reflect the views, opinions, policies, or positions of Permanent Equity Management, LLC, its officers, directors, employees, affiliates, or portfolio companies, or of any person or entity with whom the author may be affiliated. Permanent Equity Management, LLC makes no representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the accuracy, completeness, timeliness, or suitability of the information contained herein and expressly disclaims any liability for errors or omissions.

This publication is not, and should not be construed as, an offer to sell, a solicitation of an offer to buy, or a recommendation of any security, financial instrument, or other product. It does not form the basis of any contract and does not create a fiduciary, advisory, or client relationship with Permanent Equity Management, LLC. Any examples or references to third-party content are for illustrative purposes only and do not constitute an endorsement. Permanent Equity Management, LLC is not responsible for the availability, accuracy, or content of third-party materials. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Any forward-looking statements are inherently uncertain and subject to change.