Sleep, Recovery, and Stress Management: Vital Tools for Staying in the Game

It all begins with an idea.

From Director of Health Alex Maples

In a fast paced world that shows no signs of slowing down it can feel crazy to prioritize downtime. But the faster the world gets, the more vital it is to intentionally unplug and recharge. If we get caught in the trap of “more more more,” we end up operating at a deficit – and never see our true potential.

Taking time away can feel like falling behind. In reality, it’s what gives you the energy to keep pace. With the performance benefits of sleep, recovery, and better stress management, the reality is you can’t afford not to make them a priority. Think of these habits as maintenance: a small, regular expense that protects every other investment.

Sleep: The Cornerstone of Physical and Mental Recovery

Sleep is the foundation of recovery, both mentally and physically. From emotional regulation and cognitive performance to actually laying down the improvements you chased in the gym, sleep isn’t an afterthought. It’s the work behind the work.

What It Does

Rewiring Memory and Skills: Brain Performance

Memory consolidation and synaptic “down selection”: During slow-wave NREM, new memories are replayed and integrated. Ditching unnecessary fluff and consolidating the core learnings keeping the brain efficient. Result: better learning and recall tomorrow.

Motor Learning Upgrades: Late NREM sleep predicts gains in fine motor tasks. REM then further tunes sensorimotor programs. Ever get stuck on a skill then nail it the next day? Sleep puts the pieces together after you practice.

Emotional Calibration: Mental Resilience

REM sleep reduces next-day amygdala reactivity to prior emotional events and restores prefrontal control, supporting calmer decision-making under stress.

Physical Recovery: Anabolic Signaling and Tissue Repair

Growth Hormone/ IGF-1 & Testosterone rhythms. Deep sleep is tightly coupled to Growth Hormone Pulsatility; overnight endocrine patterns favor protein synthesis, connective-tissue repair, and training adaptation. Translation: the signal you send in training is built while you sleep.

Metabolic Control: Fuel Use & Body Composition

Even a week of modest restriction reduces insulin sensitivity; a single short night can move you toward insulin resistance. Short sleep lowers leptin (satiety), raises ghrelin (hunger), driving food cravings and making overeating more likely.

Readiness: Autonomic & Cardiovascular Reset

NREM sleep shifts the body into parasympathetic “rest and digest.” Heart rate and blood pressure drop, providing a nightly “cardiovascular holiday.”

Performance: Vigilance, Reaction Time and Injury Risk

Sleep restriction reliably degrades sustained attention and processing speed, undermining decision speed and accuracy.

In athletes, less sleep is associated with higher musculoskeletal injuries. Think slower reaction time, worse motor control, and poorer tissue recovery.

Walking: A Simple, Powerful Recovery Tool

Walking is widely accessible, adds to your recovery bank, and pays off without having to walk 10,000 miles.

Blood flow: Gentle contractions while walking act as a skeletal‑muscle “pump” that pushes venous blood back to the heart.

Short bouts of walking (3-5 minutes) counter endothelial dysfunction caused by prolonged sitting.

A healthy endothelium (the “smart lining” of blood vessels) opens and closes flow on demand and keeps surfaces slick – meaning less plaque and clot risk.

Improved glucose clearance: A 10-15 minute walk after a meal reduces blood sugar spikes and low-grade inflammation risk (think type 2 diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, and rheumatoid arthritis).

Boosted mood, focus, and creativity

Even short bouts of walking improve cerebral blood flow and mood; symptoms of depression/anxiety decline with both indoor and outdoor walking.

Walking boosts performance on creative tasks (perfect for a quick reset between meetings - or, even consider a walking meeting!).

Nature Exposure: A Low-Friction Stress Relief

Attention: Even a 40-second view of greenery outperforms concrete for improved focus.

Mood: Short walks near trees (even in urban areas) reduce tension, fatigue, confusion, and anxiety.

Recovery: Patients with a nature in view had less complications and shorter hospital stays post surgery.

Proactively Managing Stress Pays Dividends

Stress is part of the game and a necessary ingredient for performance. But there’s a sweet spot. Too little stress means no focus and no action; too much systems start to fray. High stress load is tied to higher risk of all cause mortality (22%) and cardiovascular disease (31%). Plus, it compromises immunity (hello, frequent colds).

It’s not about avoiding stress; it’s about noticing when you start to drift too far out of a healthy range and using simple tools to come back into balance.

The Takeaway

Sleep, recovery, walking, nature, and a few repeatable stress tools aren’t luxuries; they’re vital infrastructure. When you protect them, everything else (from training and metabolism to thinking and mood) works better.

And, you don’t need a perfect routine. Start with one: 10 minutes of walking after lunch, a quick wind-down before bed, or three big breaths between meetings. Small, consistent deposits compound, and they’ll keep you in the game for years to come.

Meaning and Purpose

It all begins with an idea.

From Director of Health Alex Maples

A labor of love is sustainable (nothing else is).

Taking care of your body is work. Forgoing the tasty thing in front of you to keep a healthy body weight. Sweating and grunting in the gym to build muscle. Making time to move so your cardiovascular system runs smoothly. Being disciplined about getting to bed each night so you can recover and do it all again. It can feel daunting, especially at the start.

That’s why I encourage anyone building a healthy lifestyle to start by connecting their fitness and health journey to meaning and purpose. Don’t just do it because you “should.” Tie it to your ability to be effective as a parent/spouse/business owner – the roles that matter most. Then, what seems like a chore becomes the scaffolding for the life you’re building.

Aesthetics are Great, but There’s More to It

We all want to look good. But consider expanding the frame: connect body composition to the functional realities of blood sugar management, inflammation, and longevity. Managing it is a lever to support your performance now and in the future – so you can watch your kids grow up and build families of their own, get down on the floor to play with your grandchildren, or have the physical capacity to do the activities you love decades down the road.

Movement as a Celebration

Find ways to move your body that truly bring you joy: pickleball with good friends, dancing with your spouse, training to summit that mountain you’ve dreamed of. A daily foundation of movement keeps you primed for adventure and fun. When it’s fun, it stops being a task and becomes something you can’t wait to do.

Take Care of Future You

Sleep can feel like it's getting in the way. “More work to be done.” “The kids are finally down – this is my only me-time.” “One more episode.” Every night offers a barrage of choices that either hurt or help your future self. Prioritizing sleep sets tomorrow up to win. Remember how much better you feel. think, and train after a solid night's rest – it might help you resist the scroll.

Putting It Together

Widen the time horizon. One workout, one walk, or one night of sleep won’t make or break you. But ten years of small good choices vs. small bad ones? It’s the difference between creaky and capable. When things start to feel like a grind, zoom out. Re-orient to the things you really care about. Think about how much better a healthy version of you will feel and perform in those situations. Health is the quiet engine behind it all – steady deposits that compound into the life you want.

The Ins and Outs of Building Muscle

It all begins with an idea.

From Director of Health Alex Maples

TL;DR

Lift weights.

Do 5–20 reps per set; the last 2-3 reps should be challenging (with good form).

Train each muscle group with 3-10 sets, twice per week.

Don’t retrain a muscle until it’s no longer sore.

Eat enough protein: 0.6–1g per pound of desired body weight.

Get plenty of sleep.

Stay active with low-intensity movement to support recovery.

We’ve established how important adequate muscle mass is to overall health and performance. Here’s the nitty-gritty of how to actually build it.

The Three Pillars of Muscle Growth

1. Stimulus: Your body needs a reason to grow – a signal that it should prepare for greater demands. Enter resistance training. When you lift weights, tension is placed on your muscles, activating force receptors in the muscle cells. If the tension is high enough, those receptors signal your body to adapt by growing stronger and adding muscle tissue.

2. Substrate: Then, you need raw materials. Protein is essential (without it, your body can’t repair and build muscle efficiently). If you train hard but under-eat protein, your body will cannibalize existing muscle tissue to repair damaged areas – a robbing-Peter-to-pay-Paul scenario that stalls progress.

3. Rest: Lifting weights sends the signal, but growth happens during rest. After training, your body enters repair mode – especially during sleep. Without adequate recovery, you simply accumulate damage without adaptation.

Stimulus: Sending the Signal

Muscle growth is driven by mechanical tension.

Useful terms:

Rep (Repetition): One complete movement of an exercise. Each rep includes a concentric phase (muscle shortens, e.g., lifting a weight) and an eccentric phase (muscle lengthens, e.g., lowering a weight).

Set: A group of consecutive reps performed without resting.

Load: The amount of weight lifted.

Volume: Sets × reps × load = total work done.

Intensity: How close a set is to your maximum effort. Measured either as a % of your 1-rep max (1RM) or using:

RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion): Scale of 1-10 based on difficulty.

RIR (Reps in Reserve): How many more reps you could do before failure.

Frequency: How often you train a given muscle group per week.

Anatomy of a Set

Rep Range: 5-20 (scientific range extends to 30, but practicality and attention span matter)

Intensity: 65%-85% of your 1RM, or sets taken to within 1-3 reps of failure

Cue: Aim for the last 2-3 reps of each set to be heavy but manageable

The sweet spot:

To build muscle, you need all three ingredients in the training signal:

Tension (sufficient load)

Volume (enough total work)

Effort (training close enough to failure)

In practice:

Doing a single all-out rep with a very heavy load gives you plenty of tension and intensity – but it lacks volume, which is also crucial for hypertrophy.

Doing 1000 reps with next to no weight gives you volume, but it lacks sufficient tension. Plus, let’s be honest – you’d probably get so bored midway through that you'd abandon ship long before rep 1000.

Think Goldilocks: enough weight to produce tension with enough reps and sets to create volume. Practically, that looks like working in the 5-20 rep range, where the last few reps are difficult but doable and enough sets that you feel challenged but not so sore you can’t train the muscle again later in the week.

How Many Sets?

Studies suggest a very wide range (from as few as 3 sets up to as many as 52 sets per muscle group per week) can stimulate growth. But that 52-set number comes from studies focusing on a single muscle group in isolation. If you tried to apply that kind of volume across your entire body, you’d likely end up as a pile of mush by the end of the week.

For most people pursuing general health, performance, and aesthetics, a much more sustainable range is:

6-20 sets per muscle group per week

Spread across 2-3 training sessions

Adjust by outcomes. Increase when:

You’re not wrecked when it’s time to train again.

Strength/rep quality improves week over week.

You feel recovered and motivated.

Remember: Volume needs are individual. Some people grow well with fewer sets, while others may need more to see progress. Tinker and adjust.

A Simple Starting Point

When working with beginners, I often start with two full-body workouts per week. Each session includes 3 sets of 4 compound exercises:

Push (chest/triceps)

Pull (back/biceps)

Lower Body: Quad-dominant + Hip-dominant

To save time and boost efficiency, I recommend antagonist supersets: pairing two exercises that target opposing muscle groups (e.g., a push and a pull). While one group works, the other rests, cutting down on total gym time and adding a touch of cardio.

Sample Beginner Program

Day 1:

3x Superset:

Incline Dumbbell Press (chest/triceps) – 8-12 reps

Leg Curl (hamstrings) – 8-12 reps

3x Superset:

Walking Lunge (quads/glutes) – 8-12 reps

Lat Pulldown (back/biceps) – 8-12 reps

Day 2:

3x Superset:

Flat Dumbbell Press (chest/triceps) – 10-15 reps

Romanian Deadlift (glutes/hamstrings) – 8-12 reps

3x Superset:

Goblet Squat or Barbell Squat (quads) – 8-12 reps

Single Arm Dumbbell Row (back/biceps) – 10-15 reps

It’s simple, scalable, and covers all major muscle groups in 30-45 minutes. If you do just this consistently, gradually increase the weights over time, and eat well, you’ll get 80% of the benefits lifting has to offer.

There are endless training splits and exercise variations out there, but for general health, this is more than enough. Get strong. Stay consistent. Build muscle.

Substrate: Building Blocks for Growth

Muscle doesn’t materialize out of thin air. Once you send the signal with training, your body needs raw materials to build new tissue – and that starts with what’s on your plate.

The star of the show here is protein, which provides the amino acids your body uses to repair and build muscle fibers. Without enough of it, you can train perfectly and still get nowhere – your body will just recycle amino acids from other tissues.

How Much Protein Do You Need?

A good rule of thumb:

0.6-1 gram of protein per pound of your ideal body weight.

If you're overweight, use a goal weight to guide your intake.

If you're lean and trying to build, use your current weight or slightly above.

Most people fall in the 100-180g/day range depending on size and goals.

Pro tip: Spread protein evenly across 3-5 meals per day to optimize muscle protein synthesis.

Protein is king, but it's not a solo act.

To support recovery and growth, you also need:

Adequate calories overall – If you’re under-eating, your body won’t prioritize muscle building. But if you’re overweight and trying to lose fat, good news: you already have extra calories on board – in the form of stored body fat. Your body can tap into those reserves to fuel the muscle-building process.

Carbs – Fuel your muscles and your brain. They replenish glycogen stores, which is especially important if you’re training hard or frequently. Carbs have been demonized to death in fitness circles, but if performance is the goal, they’re not the enemy – they’re a powerful tool in a balanced diet.

Healthy fats – Support hormone production, joint health, and overall cellular function. A good baseline is 0.3 grams per pound of goal body weight per day. Dip too far below that, and you may not have enough raw materials for optimal hormone production – especially testosterone and other key anabolic hormones.

You can be flexible with carbs and fats based on your preferences. But, if you’re skipping the protein, you’re leaving gains on the table.

Practical Tips

Track protein intake at least for a week to get a sense of where you stand.

Front-load your day with a high-protein breakfast – don’t play catch-up at dinner.

Use snacks strategically (e.g., Greek yogurt, jerky, protein shakes) to hit your daily target.

Special Considerations: When You May Need a Caloric Surplus

If you're lean and undermuscled, or you’ve been training for a while and want to continue building muscle, there comes a point where a caloric surplus becomes necessary. Gaining muscle requires energy – not just protein, but total fuel.

Beginners can often build muscle without gaining weight (aka "newbie gains").

Overweight individuals can often gain muscle while losing fat, thanks to built-in energy reserves.

But for trained, lean individuals, further progress almost always requires eating more than you burn.

At this stage, you may benefit from a dedicated bulking phase, where you intentionally gain a modest amount of weight (e.g., 0.25-0.5 lbs per week). This gives your body the resources to build muscle efficiently, without excessive fat gain.

For more advanced lifters chasing their genetic potential (not just “enough” muscle for health, but the upper ceiling of performance) this may also mean cycling between bulking and cutting phases over time.

This level of planning isn’t necessary for everyone. But if you're serious about maximizing size and strength, it's something to consider.

Rest & Recovery: Where the Magic Actually Happens

You’ve lifted. You’ve fueled. Now it’s time to grow.

It’s easy to fall into the trap of constantly asking, “What else can I do?” More workouts, more supplements, more hacks. But when it comes to building muscle, sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is… nothing. Or more specifically: rest strategically.

Why Recovery Matters

Training sends the signal. Nutrition provides the building blocks. But recovery is where the actual construction happens.

Every time you lift, you create microscopic damage in your muscle fibers. That’s not a bad thing – it’s the stimulus your body needs to grow stronger. But without adequate recovery, you’re just piling stress on top of stress, and eventually your body stops adapting and starts breaking down.

When you rest, your body repairs that damage, making your muscles stronger, thicker, and more resilient than before. No recovery? No progress.

Sleep: The Underrated Linchpin

If you could bottle the effects of high-quality sleep and sell it, it would outsell protein powder and pre-workout combined.

Most muscle repair and growth happens during deep sleep, particularly during slow-wave sleep stages.

Growth hormone (A key signal for repair) is released in its highest concentrations during sleep.

Testosterone (a key contributor to anabolism) also rises during sleep.

Poor sleep increases cortisol (your stress hormone), which interferes with muscle repair, blunts testosterone, and increases the risk of fat gain.

Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. If you’re training hard or under high life stress, lean toward the higher end.

Simple tips that go a long way:

Keep a consistent sleep schedule (yes, even on weekends).

Limit screens and bright lights 1-2 hours before bed.

Cool, dark, quiet room = sleep superpowers.

Active Recovery: Move Light, Recover Hard

Rest doesn’t mean becoming one with your couch. In fact, light movement can enhance recovery by increasing circulation, reducing soreness, and promoting lymphatic drainage.

Think:

Easy walks

Light cycling

Yoga or stretching

Mobility work

This type of movement increases blood flow without adding more fatigue, which can speed up the repair process and help you bounce back stronger.

Bonus: It also helps regulate your nervous system – especially important if you’re dealing with stress (and who isn’t?).

The Big Picture

Building muscle isn’t just about doing more. It’s about doing enough and then stepping back to let your body respond.

If you're constantly sore, dragging through workouts, or not making progress despite "doing everything right," it might be time to train less, sleep more, and move gently on your off days.

Strategic recovery isn’t laziness – it’s intelligent training.

The Dieting Dilemma: Why Finding Your Sweet Spot Matters

It all begins with an idea.

From Director of Health Alex Maples

The Rush to Results

Many of us approach dieting like ripping off a bandage – the faster, the better. I get it, I'm guilty as well. Intentionally depriving ourselves is hard, and the thought of doing so longer than necessary is maddening. So the faster the better…right?

Well maybe. There’s a common theme when thinking about fat loss: Aim for sweet spots, not extremes.

The Slow-and-Steady Struggle

Dieting slowly might be the healthiest move on paper (and for your body), but maintaining a tiny deficit for months can be excruciating. The margin for error is small, meticulous tracking gets tedious, and progress is slow enough that it’s difficult to tell if anything’s changing.

The Danger of Drastic Deficits

The other end of the spectrum is to go hard and rush to the finish line. Tempting, there can be some pretty nasty tradeoffs.

A deep caloric deficit is stressful on our bodies. We’re literally taking away the substrate our bodies use to function and asking our bodies to access the energy we have stored as body fat. Do that at a slow to moderate pace, no big deal. Do that quickly? The body starts to worry. From a survival perspective, an extreme dip in the calories coming in spells big trouble.

Your Body’s Priorities: Survival First

Humans, like all living creatures, have two fundamental drivers:

Survival

Reproduction

When survival is taken care of, we can put resources towards the second (grr baby). But when survival feels threatened, the body reroutes resources toward finding food and away from, well, everything else.

Even when, intellectually, we know that we’re not at risk of starving while dieting, our bodies don't. The deeper and more sustained the restriction of energy, the more generations of biological hardwiring think our survival is at risk. That means the less we’re going to spend resources on anything that doesn't immediately work towards us surviving this (artificial, self-imposed) famine.

In men, testosterone will drop – and with it sexual desire. Women will stop menstruating, and their bodies will no longer prepare for pregnancy each month.

It's a genius design. Without enough available resources around to ensure survival, our bodies put the kibosh on reproducing because the likelihood of offspring surviving in a real resource-scarce environment drops dramatically.

System-Wide Conservation: Body and Mind Under Siege

Sex drive isn’t the only thing affected by the hormonal cascade resulting from a (again, artificial) resource crisis. The perceived threat of starvation triggers a comprehensive energy-conservation strategy across your physiology – including both physical and cognitive functions.

Physical Energy Conservation

Reduced Basal Metabolic Rate: Your body becomes remarkably efficient with calories by lowering your BMR (the amount of energy needed just to keep your organs functioning). The upshot is that you burn significantly fewer calories, even at complete rest.

Decreased Physical Performance: Strength, endurance, and recovery capacity dip as your body diverts energy away from muscle tissue maintenance. Workouts that once felt manageable become increasingly difficult.

Fatigue and Lethargy: Your brain actively generates feelings of tiredness to discourage movement, reducing what scientists call NEAT (Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis) – all the small, spontaneous movements that typically burn calories throughout your day.

Cold Intolerance: Body temperature regulation requires a lot of energy. When resources are scarce, your brain reduces circulation to extremities and lowers core temperature slightly, making you feel perpetually cold.

Cognitive Prioritization

While these physical changes are occurring, your brain, which normally consumes about 20% of your total energy despite being only 2% of your body weight, undergoes its own resource allocation strategy:

Impaired Concentration: Your brain rations glucose to essentials, making concentration on anything unrelated to food or immediate survival harder.

Decision Fatigue: Complex decision-making and your capacity for nuanced thinking and willpower dramatically decline, explaining why dietary compliance becomes progressively harder.

Cognitive Narrowing: You hyperfocus on food as your brain prioritizes finding nourishment. Hence why most people on a diet become preoccupied with meals, recipes, and eating.

Memory Issues: Working memory and cognitive processing speed decline as your brain directs limited energy to more survival-critical functions.

Mood Disturbances: Serotonin/dopamine balance can be disrupted, triggering increased irritability, anxiety, and depression. (At least these mood changes aren't character flaws but direct biological responses to perceived threat?)

All these adaptations occur through precise biological mechanisms. Stress hormones like cortisol increase (promoting fat storage and muscle breakdown), while thyroid hormones decrease (slowing metabolism). Blood glucose is carefully regulated to ensure your brain receives adequate, if limited, fuel. Your entire endocrine system recalibrates to preserve your life – at the cost of your quality of life.

The Fat Loss Pendulum: Why Diets Break

Rebound is common. 80% of people who lose a significant amount of weight regain the weight. 30-60% of them end up heavier than before.

Think of a pendulum: the harder you swing in one direction, the more the momentum is going to swing back against you on the return trip. If you’re super aggressive and restrictive with your diet, when you let your foot off the gas your appetite and hunger will be through the roof.

Part of making a sustainable approach is about creating less momentum. That means either reducing the total force, or shortening the distance the pendulum travels.

Finding Your Sweet Spot

I don't like the low and slow approach. I would rather be more uncomfortable for a shorter period than be a little uncomfortable for a long period. But, I also recognize that if I am too aggressive, my mood, thinking, training, and, yes, sex drive all suffer.

Two strategies that balance results with sanity:

Strategy 1: The Undulating Deficit

The undulating deficit is pretty straight forward:

5 days of an aggressive deficit (e.g., 500-750 calories below maintenance)

2 days of maintenance or slightly above maintenance

Real-world example: If your maintenance calories are 2,500, you might eat 1,750-2,000 calories Monday through Friday, then 2,500-2,700 calories on Saturday and Sunday.

This approach allows me to go hard when I'm going, and then take a breather and recharge a little before I go back in. I personally like to do this approach with my weekly schedule. Dieting hard during the week, when I am occupied with work and other responsibilities, and then eating more on the weekends, when I am less busy and more likely to have social events like date nights or family gatherings.

The tricky part is not viewing this as a license to eat anything I want, but rather just having more room for some pleasurable foods or things outside of my typical diet. For example, having that glass of wine with dinner or enjoying dessert after a meal out.

Strategy 2: Diet Sprint/Minicut

If you want to “rip the bandage,” another option is a diet sprint or minicut. Unlike with the undulating deficit, here we’re aiming to keep our calories level through the entirety of the diet. It’s just shorter.

Instead of maintaining a moderate deficit for 12 weeks, aim for a more aggressive deficit for 3-6 weeks. After that, there’s an equal amount of time at maintenance. If you still have more you’d like to lose, do it again.

Real-world example: A 4-week sprint at a 750-calorie deficit (for someone with 2,500 maintenance calories, that's 1,750 daily), followed by 4 weeks at maintenance (2,500), then another sprint if needed.

Both of these approaches allow for a more aggressive approach, but they put limits on the amount of time your body is under higher stress. The idea is to mitigate the stress of dieting by not being chronically underfed. Instead your body gets time to cool off and recover. And, you get a mental break.

The Long Game Approach to Lasting Results

Fat loss is a long game whether we like it or not. Sure it's physiologically possible to lose a ton of weight quickly. But the harder we push, the harder the body tends to push back.

It's okay to be aggressive, but you have to plan for the pendulum: build in breaks, watch your recovery, and adjust when signals (sleep, mood, training quality) slide.

Sustainable progress, even if it's slower than you'd like, beats rapid results that quickly reverse themselves. Find your personal sweet spot between aggressive deficits and strategic breaks, and you'll build a healthier relationship with food while achieving the body composition changes you're after.

Try one of these approaches for the next month and see how your body responds. The most effective diet isn't usually the most extreme one; it's the one you can actually stick with long enough to see lasting change.

The First Principles of Health and Fitness

It all begins with an idea.

From Director of Health Alex Maples

You’re busy. You’ve spent a lifetime dialing in where and how to spend your time, effort, and resources to get the best results: in your business, with your investments, with your family, and maybe in your fitness journey. There’s a lot of noise in the fitness space, and there’s nothing more frustrating than wasting your time and energy on something that doesn’t get you the results you want.

Welcome to First Principles, a series of posts and resources to help you focus on what truly moves the needle so the energy you spend improving your health is as efficient and effective as possible.

We’ll dive into four main pillars – the foundations that provide the greatest return on our investment when it comes to building lasting health. Here’s the quick overview:

Body Composition: What You’re Made Of Matters

You probably know that body composition matters. (Look better? Check. Be healthier? Double check.)

But your ratio of muscle to fat isn’t just about aesthetics or a standalone marker of “health” – it’s metabolic currency. More muscle improves insulin sensitivity, bone density, and resting metabolic rate. Too much fat, especially around your organs (visceral fat), drives inflammation and increases the risk for chronic disease. Improving lean mass while reducing fat is strongly associated with lower all-cause mortality.

Think of muscle as a long-term asset – it keeps you strong, mobile, and resilient as you age. But, we all lose muscle as we age. Building more now helps retain more later, helping you stay upright and independent.

Fat, on the other hand, is the cost of doing business. Sometimes it accumulates as a byproduct of growth. That’s okay – it's part of the process. But eventually, the books need to be balanced. That’s where fat loss phases come in. They’re financial audits – strategic, intentional efforts to trim the excess and keep the health account in the black.

Cardiorespiratory Fitness: The Engine Under the Hood

Often relegated to the realm of endurance sports nuts, cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) is in fact one of the strongest predictors of lifespan. VO₂ max, a key measure of CRF, reflects how well your body delivers and uses oxygen – a capability every cell in your body depends on.

Good CRF helps you think clearly, recover faster, and handle more physical and mental stress. It lowers the risk of heart disease, stroke, and even some cancers. (And, yes, it lets you run that ultra if you want to.)

The best part? You don’t need to run marathons. Consistent zone 2 cardio (think brisk walking, cycling, rowing at a conversational pace), along with occasional higher-intensity sessions, can make a profound difference.

Sleep and Recovery: Your Built-in Repair System

When you’re trying to get healthier, the first instinct (like many people’s) might be to add more: more workouts, more supplements, more productivity hacks. But sometimes the most powerful lever is knowing when to rest.

Without quality sleep and recovery, you don’t adapt – you just accumulate stress. Recovery is when your body rebuilds, your hormones rebalance, and your mind processes the world around you.

Lack of sleep impairs glucose metabolism, weakens the immune system, disrupts mood, and fogs cognitive function. Deep sleep, in particular, is essential for physical restoration.

When you train, you write the check. Recovery is when you cash it.

Stress Management and Purpose: The Psychological Core

You can’t out-lift chronic stress or out-supplement a lack of meaning. (Read that again.)

Stress isn’t inherently bad – if you have goals or care about anything (i.e., you’re human), stress comes with the territory. In fact, too little stress can be just as dangerous, often signaling a lack of purpose or engagement.The real key is learning to manage and channel it.

Chronic stress disrupts your hormones, appetite, sleep, and focus. But when stress is anchored to purpose, it becomes fuel instead of friction. A clear why is a GPS for your nervous system. It helps you reframe discomfort as growth, and it keeps you aligned when life gets messy.

You build resilience just like you build strength: through consistent training. Breathwork, boundaries, meaningful relationships, movement, time in nature – these are essential tools, not luxuries.

It’s a System, Not a Checklist

These four pillars don’t exist in isolation – they support and amplify one another. Better sleep enhances body composition. Cardio improves stress tolerance. Purpose sustains consistency.

Health isn’t about chasing perfection – it’s about mastering the fundamentals and building a system that works for your real life.

This series is designed to equip you with practical tools and mental models to strengthen the core pillars of health. You’ll learn how to filter out the noise, focus on what actually matters, and tailor a system that fits your goals and lifestyle. Whether you want a quick overview or a deep dive, you’ll find both the why and the how, along with a clear roadmap to support not just your health, but your life as a whole.

What You’re Made of Matters

It all begins with an idea.

From Director of Health Alex Maples

Your ratio of muscle to fat isn’t just about looks. Body composition shapes how your body functions and how long (and well) you live. In fact, outside of not smoking, few factors impact your long-term health outcomes more.

There are two main levers to improve body composition: Building muscle and losing fat. Simple, not easy. We’ll hit the “how” shortly; first, here’s why these levers matter.

Why Muscle Matters

Muscle isn’t just for athletes or bodybuilders. It’s a critical asset that protects your health and independence as you age. Call it a “longevity organ.”

Here’s what the research has to say about it:

Lower All-Cause Mortality

Adults over 55 with higher muscle mass had a 20–30% lower risk of death over 10 years. In plain English: more muscle, better odds over time.Better Metabolic Health

Muscle is the primary storage site for glucose. Each 10% increase in skeletal muscle index reduced insulin resistance by 11% and cut the risk of type 2 diabetes by 12%.Cardiovascular Protection

Muscle supports healthy cholesterol, blood pressure, and vascular function. Research has shown a 25% lower risk of cardiovascular events in those with higher muscle mass.Bone Density & Fall Prevention

Muscle strengthens bone and stabilizes joints. Resistance training reduces fracture and fall risk by over 30%, especially in older adults.

Mental & Cognitive Health

More muscle is linked to lower depression and cognitive decline. Multiple studies show reduced risk of depression (20%) and cognitive impairment (30%) in those with greater muscle mass.

Use It or Lose It

Without intervention (i.e., training), most people begin losing muscle mass by midlife (≈30s–40s) at roughly 0.4–0.8% per year, with faster losses in later decades (≈0.6–1%/yr by the 70s). Strength declines more rapidly (≈2.5–4%/yr in the 70s). The result: accelerated weakness and frailty, raising risks to independence.

But it’s not inevitable. Resistance training can not only prevent muscle loss, it can reverse it – even into your 50s and beyond. Think of muscle as your health retirement account. The more you invest early, the more protected and resilient you’ll be later in life. And just like financial savings, it’s never too late to start making smart deposits.

Why Excess Body Fat Harms Health

Carrying excess body fat – especially visceral fat (the kind that surrounds organs in the abdomen) – raises your risk for nearly every major chronic condition:

Increased Mortality

A meta-analysis of 10 million+ people found each 5-point increase in BMI above 25 raised mortality by 31%.High Blood Pressure

Excess adiposity is estimated to account for ~65%-75% of primary hypertension; in Framingham, 78% of essential hypertension in men and 65% in women was attributable to obesity.Heart Disease

A meta-analysis found that higher BMI and larger waist circumference are linked with greater risk of heart failure and other cardiovascular events.Metabolic Dysfunction

Excess fat impairs insulin sensitivity and spikes your risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome. A 5 kg/m² BMI increase often more than doubles your diabetes risk.Cancer Risk

Excess body fat is linked to 13 types of cancer in epidemiologic research.Mental Health & Cognition

Obesity increases the risk of depression (32%) and increases risk of cognitive decline with aging.Joint and Respiratory Issues

Excess weight stresses joints and narrows airways, raising the risk for arthritis, sleep apnea, and asthma.

How to Improve Body Composition

Reduce Body Fat

Create a modest calorie deficit with food + movement (think sustainable, not crash).

Focus on nutrient-dense, protein-forward meals to stay full and preserve muscle.

Track progress with trend-friendly tools (BIA scales or DEXA scans) – not just weight.

Build Muscle

Stimulus: Resistance training (3–5x per week) is key to signaling your body to grow muscle.

Substrate: Aim for 0.6–1g of protein per pound of goal body weight daily.

Rest: Recovery allows muscles to rebuild stronger. Prioritize sleep and manage stress so you can come back tomorrow.

Bonus: If you're new to lifting, you may experience “body recomposition” – losing fat and gaining muscle simultaneously.

Where Should You Be?

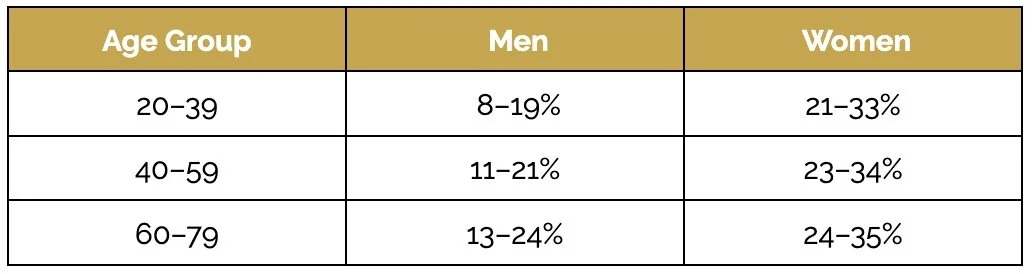

“Optimal” varies, but these are general body fat ranges associated with good health:

Going too low may suppress hormones and impair function – so leanness for the sake of leanness isn’t the goal. Sustainable health is.

How to Measure Your Body Fat

Knowing where you stand is essential for improving body composition. While there are many methods out there, the two most accessible and practical options are DEXA scans and BIA (bioelectrical impedance analysis) scales. Each has its pros and cons – understanding both will help you use them wisely.

DEXA Scan: The Gold Standard

What it is:

A medical imaging scan that measures bone density, lean tissue, and fat mass with a high level of precision.

Pros:

High accuracy: Margin of error is typically around 1–3%.

Regional data: Shows fat distribution (e.g., visceral vs. subcutaneous).

Bone density insights: Valuable information for aging and injury prevention.

Cons:

Cost: Typically $50–$150 per scan.

Access: Must be done in a clinical or wellness setting.

Radiation: Very low dose, safe for periodic use but not for frequent tracking.

Best for: Establishing a reliable baseline 1-2 times per year.

BIA Scales: Convenient, but Often Underestimate

A small electrical current estimates your body fat percentage based on conductivity (water-rich muscle tissue conducts electricity better than fat).

Pros:

At-home convenience: Easy to use consistently.

Affordable: Many good options under $100.

Good for trend tracking over time with consistent conditions.

Cons:

Less accurate: Error margins range from 3–8% or more.

Underestimates BF%, especially in lean or muscular individuals.

Affected by hydration, food intake, and time of day.

Limited detection: Most home devices use only hands or feet, which can miss central fat stores.

Example: If your BIA scale says 12%, you might actually be closer to 15-17% depending on your muscle mass and hydration.

How to Use BIA Effectively

Despite its flaws, BIA can still be a valuable tool if you use it the right way:

Measure under consistent conditions: same time of day (ideally in the morning, fasted, and post-bathroom).

Track the weekly average, not individual daily readings.

Look for trends over time, not absolute values.

Pair with occasional DEXA scans to recalibrate your sense of what your scale is really showing you.

Closing Thoughts

Muscle supports everything from strength and mobility to mood and metabolism. Excess body fat compromises them all. By improving your body composition, you're not just changing how you look (although when you feel good about how you look, you’ll perform better and have more confidence). You're investing in the duration and quality of your life for the long term.

The Engine Under the Hood

It all begins with an idea.

From Director of Health Alex Maples

When most people think of cardio, they think of calorie burn. And while it does burn calories, that’s just one tiny part of the picture. In fact, if your primary goal is weight or fat loss, cardio may not even be the most effective tool (see Body Composition: What You’re Made of Matters).

Here’s the real headline: Cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) offers a huge return on investment that has nothing to do with calorie burn. From heart health to brain function to how long (and how well) you live, its impact is both broad and profound. It’s not just about burning energy. It’s about building capacity.

CRF and Your Baseline Operating System

Cardiorespiratory Fitness (CRF) is your body's ability to deliver oxygen to muscles during sustained physical activity. It’s a measure of how well your heart, lungs, blood vessels, and muscles all work together as a team. Improve CRF, and you upgrade your default state – not just your workouts. Here’s what that means:

Lower Resting Heart Rate & Blood Pressure

With higher CRF, your heart becomes more efficient. It pumps more blood per beat, so it doesn't need to work as hard at rest. In other words, a stronger engine idles lower:

Resting heart rate often lands around 50-60 bpm in fit individuals.

Blood pressure trends lower.

Blood flow to the brain and organs improves.

This improved efficiency makes everyday tasks (climbing stairs, walking, standing for long periods) feel easier. You’re simply operating with a better engine.

More Resilient Nervous System

Higher CRF enhances autonomic balance, boosting parasympathetic tone (your “rest and recover” system). That means:

You handle stress better.

You recover faster from both workouts and life events.

Heart rate variability (HRV) tends to improve (a marker of adaptability and nervous system health).

Protective Effects of High CRF

Lifespan extension: Significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality, with no upper limit of benefit (i.e., benefits stack as fitness improves).

Reduced cardiovascular risk: Lower risk of heart disease, stroke, hypertension.

Improved metabolic health: CRF improves insulin sensitivity and blood sugar regulation.

Brain benefits: Better mood and memory, plus protection against cognitive decline.

Consequences of Low CRF

Low CRF doesn’t just make life harder – it makes it shorter.

Increased mortality risk: Worse overall health outcomes – on par with major risk factors like smoking, diabetes, or hypertension.

Fatigue and poor recovery: Less energy for daily life and workouts, and decreased stress resilience.

Higher disease burden: Increased risk of cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Faster aging curve: Mitochondrial decline, reduced capacity to handle physical and psychological stress.

How to Improve CRF

First and foremost, get moving! Nuance helps, but movement is the foundation of good CRF. And, it doesn’t matter how you do it – you can walk, hike, bike, run, row, paddle, swim, dance, jump rope, or play sports. Explore until you find a few that you actually enjoy. Joy is compliance, and compliance compounds – like steady deposits in a well-run account.

The Takeaway

Cardio is more than a calorie incinerator – it’s a capacity builder. Better CRF means that everything else that matters (thinking, sleeping, training, even stress management) gets easier. If strength training writes the check, aerobic fitness is the cash flow that keeps your whole system liquid.