Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions delivered to your inbox.

Day 2

At Amazon it’s supposed to always be Day 1. What this means is that anything is possible if you stay “constantly curious, nimble, and experimental.”

As for day 2, well, that’s what you want to avoid. Because as founder and then CEO Jeff Bezos joked at an all-hands meeting, day 2 “is stasis followed by irrelevance followed by excruciating painful decline followed by death.” And as someone who sits here 40-plus years old with acute tennis elbow after getting smoked in a casual game of pickleball, that hits a little too close to home. But does day 2 get a bad rap?

I thought about this recently when my daughter got a new phone. See, before she traded in her old phone, she made sure to transfer all of the photos on it that she wanted to keep. I was looking at those pictures with her as she did this and among them were her as a 3- and 4- and 5-year-old playing soccer with me coaching in the background. I about cried (which is becoming a recurring theme here) reliving those moments.

One takeaway from that is that sentimentality increases exponentially with age. Another, since she wanted to save them, is that teenagers may actually care about stuff (though the jury is still out on that)...

But she was offended when I remarked that I missed those days. Because why would I miss those days when I have these days? And that was an interesting question because I love these days. What’s different from then to now, though, is (1) we have fewer days left and so therefore (2) there is less open-ended-ness.

In other words, and to be brutally honest, even though I try to be curious, nimble, and experimental, it’s not day 1 for me anymore (and also not for Amazon either). I’ve done things and made decisions that specifically preclude me from doing other things and making other decisions which means that not anything is possible for me. That said, it oversimplifies it (I hope) to say that if I’m on to day 2 (or 3 or 4) with a diminished opportunity set that I’m headed for irrelevance and excruciating painful decline.

That’s because here on day 2 (or 3 or 4) I’m building on previous choices made to take a step (or steps) forward. So while my scope of opportunity is narrowing, the magnitude of significance of what’s left to do is growing.

When I previously about cried prior to spring break, I wrote that you or the world is always moving on, and I stand by that. But the thing about that statement is that it’s simultaneously something to be lamented and celebrated. To wit, I miss my little kids, but I love my kids.

So the thing to avoid isn’t day 2 because day 2 (or 3 or 4) is inevitable. The thing to avoid, as Bezos rightly notes, is stasis.

So wherever you are, personally or professionally, recognize that you won’t be there for long and further that you can’t (and hopefully don’t want to) go back to where you once were. You’re headed somewhere next and that also means not being headed to an increasing number of other places. For that to be something to celebrate and not lament, be intentional with your investments of – and in – time, capital, opportunities, and people. You can’t do it all, but do what you can.

Here’s to Day 2.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

These Are Still Worth Reading

Felix shot me a note not long ago asking if I had to train myself in investing today, what books would I read? This, of course, revealed Felix as a relatively recent reader since I touched on this topic way back in season one. But since most of you are relatively recent readers (building an audience is a slow burn) and since Felix asked, I thought I’d revisit it.

First, a point about investing. For me, successful investing requires taking insufficient information and synthesizing it with what you know about the world to make bets on people that are more likely than not to increase in value at a rate that exceeds what you’d achieve by getting out of bed everyday and going through the motions. If you agree, then investing methodologies aren’t necessarily what matters most to doing it (though you do need to be numerate and know enough about financing and accounting to be dangerous), but rather knowledge and understanding of how both you and others are wired and the implications of that for how the world works. This is why my book recommendations for aspiring investors are pretty unconventional. They are: The Classic Guide to Better Writing by Rudolf Flesch, Deep Survival by Laurence Gonzales, and A Sick Day for Amos McGee (a children’s book!) by Philip C. Stead.

A good question is why are these three odd books my recommendations? The reason is that together they can help you understand and communicate well in stressful situations with incomplete information while remaining kind, caring, and curious. And there you have it. That’s investing.

Yet another aspect to successful investing is that you have to be constantly updating your priors (shoutout Thomas Bayes). To that end, I also recommend investors read a lot of contemporaneous stuff every day. These picks include X nee Twitter, Matt Levine’s Money Stuff, The Wall Street Journal, newspapers from different foreign cities, recent SEC enforcement actions, and newly published papers in the field of decision science.

Yet if you twist my arm, you can also get me to recommend some canonical investing and business books. None of these are likely anything you haven’t already heard of, but if you know someone who hasn’t read them and wants to get into this field, they always make great gifts. They are (in no particular order):

The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham

Poor Charlie’s Almanack by Charlie Munger and edited by Peter Kaufman

Berkshire Hathaway Letters to Shareholders by Warren Buffett

The House of Morgan by Ron Chernow

The Fish that Ate the Whale by Rich Cohen

Business Adventures by John Brooks

The Big Short by Michael Lewis

The Match King by Frank Partnoy

Shoe Dog by Phil Knight

Expectations Investing by Michael Mauboussin

Unreasonable Hospitality by Will Guidara

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman

What’d I miss?

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Do you Care to Be Curious?

I grew up in New York, but spent the most formative years of my life (17 to 37) in Washington, DC. In other words, I landed there a kid out of high school and left a home-owning parent. I’m not sure what gets more formative than that.

Anyway, I had the opportunity to travel back there recently, and that prompted some reflection. I saw some places I’d taken my kids way back when that were completely the same and then some others that were completely different. What’s true is that either you or the world is always moving on.

But rather than make this a big piece about big things like that, I’m going to make it a small piece about me (my favorite topic!) and about the compliment I got from my friend and mentor Bill Mann when we went to visit and have dinner with him at his new pub in Vienna, VA (shoutout Hawk & Griffin…get the fish & chips).

First of all, I love Bill and the fact that he now owns a pub. We should all aspire to be a part of a neighborhood gathering place we adore, and the fact that he hosts a quiz night there every Wednesday made me envious (the only person that might take him down should they compete in that venue is my son, the 3x GeoBee champion).

But as Bill was treating us to fish & chips Emily (who else?) asked him to tell some embarrassing stories about me. Bill demurred (despite many obvious candidates) and so Emily, switching gears, asked if he ever thought this kid from NY via DC would ever find himself in mid-MO doing a prescribed burn of a native wildflower meadow (which is something I do annually because when we moved to Missouri, we moved to Missouri)?

Then Bill, after ruing the fact that he still hasn’t traveled out to help (shoutout Clayton and James who do, though admittedly they live here), said, “I didn’t know where this kid was going to end up, but ever since I’ve known him he has cared about knowing how things work and dove into finding out. So does it surprise me that he is now doing a burn in Missouri? No.”

I about cried. It was one of the nicest things I’ve ever heard said about me.

Now, this whatever-it-is is not supposed to be about me, but since I write it, it tends to traffic in ideas I’ve learned or observed over time. One of those that I put forth a while back is that we should all care enough to be curious.

But it’s one thing to write something and another to live it, so the reason I so greatly appreciated Bill’s comment is because it confirmed that someone saw in me something I aspire to be (which is to care and be curious). And that feels good.

What are the takeaways?

One is to make sure you’re doing things that you care enough about to be curious about and therefore really dive into doing them. This means you avoid the dreaded going through the motions and ensures you will have fun while also achieving at a high level, which is something others will notice.

Another is to tell people what you see in them, and particularly so if it’s good, because it will never go unappreciated. Self-assessment is hard and imposter syndrome is a real thing we all deal with. This isn’t to say that we’re phonies (as Holden Caulfield would allege), but rather that it’s hard to be and know that you are who you want to be. But if you try to be it genuinely and consistently, the world should and will see it in time and eventually.

Finally, while this is normally where I’d say have a great weekend on this flippant Friday, it’s Spring Break! We have some plans and so therefore plan to take a few weeks off to recharge. See you on the flip side, have a great time in the meantime, and we (mostly SarahGW) promise to finish S3 (huh?), whenever it is that we come back, strong.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Drinking to Add Value

One observation that we made recently is that when we travel as a team, we have significantly more productive experiences when we share an Airbnb instead of having individual hotel rooms. The reason for that is that when we get an Airbnb we usually spend an hour or so in the common space after dinner discussing the day while it is still fresh on our minds. When we get hotel rooms, on the other hand, we tend to retire to our rooms after dinner.

In both circumstances, whether we are out in the field on a site visit for a potential deal or meeting with one of our portfolio companies, there is usually a lot to reflect on. And this isn’t to say that we do that when we get an Airbnb and don’t do it when we get hotel rooms, but rather than when we get an Airbnb, it’s a social activity and a dialogue whereas when we get hotel rooms, it’s an antisocial one and a monologue (because we draft written notes and pass them around via email or Slack).

Both of these approaches have their place, but a key learning is that we need to do both.

Back when I wrote about my process for writing Unqualified Opinions every day, I noted that that process has two phases. The first, an idea generating discovery phase with my son, is conversational and social while the second, an editing and refining phase that I do in my head while I run, is isolated and antisocial. Then I said that that makes sense because good ideas need both points of view and a point of view and added offhandedly that meetings should be organized that way as well.

More than a few people latched onto that offhand comment, with one person saying he would spend the next few days thinking about how his meetings might better employ both phases. I asked him to tell me what he figured out because to the point about Airbnbs versus hotel rooms, we haven’t hit upon a reliable, repeatable process either.

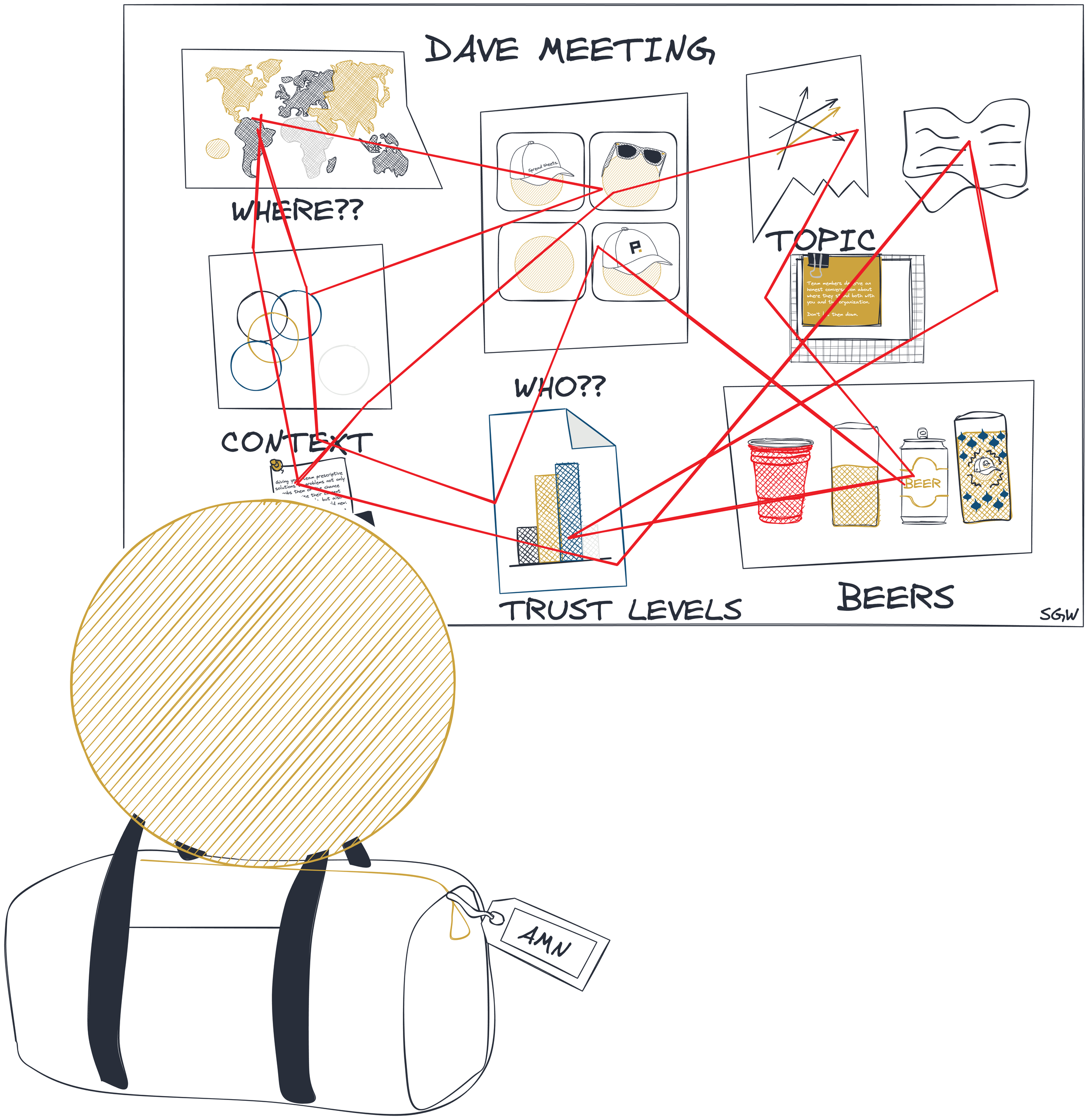

To wit, after one particularly productive conversation we had on the road recently, Mark said to the group, “I thought this conversation was particularly productive. How do we have more of them?” As we thought about that, we tried to identify the factors that contributed to that productive conversation. Here’s what we came up with:

A group that wasn’t too big, but wasn’t too small;

That had high levels of trust;

But different levels of context;

On a topic that was both recent and timely;

With nowhere to go and nothing else to do;

After having a few beers.

And when we looked at that, it seemed like a difficult set of variables to formalize without locking people in the office and forcing them to drink on short notice – which doesn’t seem like it would be productive and/or good for work/life balance.

But apparently our COO Mark is going to give it a shot, planning to schedule the first optional Permanent Equity Drinking to Add ValuE (DAVE) meeting for later this month. We’ll see how it goes.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Time to Judgment

Something we struggle with over and over again at Permanent Equity is how long to wait and watch before declaring that something is going well or poorly. And then, relative to that, how strong to push to adapt to this new and unexpected set of circumstances.

I mention this now because it’s timely. We are almost three months – or one quarter – of the way through the year, which means there is two-plus months of financial and performance data from our portfolio companies to analyze and react to. If one of them is struggling to date, should we be concerned and, if so, how concerned should we be? If, on the other hand, another is outperforming, is now the time to celebrate?

In my experience, the answers to these questions depend on three variables: time, magnitude, and trust.

For example, I had the misfortune this past season to have a rooting interest in two of the most disappointing men’s college basketball teams in America: the Missouri Tigers and the Georgetown Hoyas. Missouri, you may remember, wildly outperformed expectations last year in Coach Dennis Gates’ first and made the NCAA tournament only to run it back and go winless in SEC play in 2023-24. The Hoyas, on the other hand, parted ways with alumnus Patrick Ewing to bring in the much-heralded coach Ed Cooley from Providence only to win two games in the Big East, both over lowly DePaul.

And while it would have been inconceivable for anyone to think Dennis Gates would be on the hot seat this time last year, the magnitude of the team’s recent underperformance means that there is chatter about his job security despite his only being in the role a short time and having previously built up a lot of trust. Ed Cooley, on the other hand, still has a lot of trust given his long-term track record, but if next year isn’t better than this past one in terms of wins and losses and recruits, his seat is going to heat up as well.

Look, we can all agree that bad days happen and that they are outside of our control. Bad weeks, too. But a bad month? A bad quarter? A bad year or two?

In the case of our businesses, we see a lot of bad months, and they tend to be more noise than signal. That, I think, is common in the lower middle market. After all, it’s impractical for businesses of such a size to have the attributes, such as hedging programs, employee redundancies, and revenue visibility, that underpin stable month-to-month performance.

But bad quarters, while not necessarily anything to panic about, more times than not put the nail in the coffin of the prospect of a truly great year. And if you have two bad years in a row that, more times than not, means that something is broken and needs fixing.

Yet a lot of time (21 months to be exact) elapses between a bad quarter and a bad two years, so we’re back to the question of when to intercede and how forcefully? Because change, if it’s real change, is destabilizing, and it might have the same (or better) odds of making things worse as it does to make them better.

Let’s go back to Dennis Gates. Sure, Missouri could replace him, but he by all accounts has put together a top 10 2024 recruiting class (watch your head, Annor Boateng). Get rid of him and those kids are likely gone, so Mizzou hoops would be back to square one. In other words, I’d have enough trust to give him more time given that the magnitude of the upside next year would make up for what has been a terrible, terrible one-year measurement period.

But I could also see someone taking the other side of that argument because a year is a long time and because the in-game adjustments haven’t been great. The challenge with a decision like this, of course, is that if you make it one way or the other, you will never know how the other decision would have worked out.

So when and how, in business, in sports, or wherever, do you feel confident about how things are going? Let me know because I’ll take all the help I can get.

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Bertie’s Beer Money

You’re in rarified air as an investor if you’re able to throw shade at the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), and your auditor without fear of comeuppance. And that’s where Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett is these days, doing just that in his most recent annual letter in pointing out the pointlessness of reporting GAAP net income.

I previously wondered who generally accepted generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), and the fact remains that it’s the least worst way of tracking financial performance except for all the others.

Buffett’s gripe with GAAP has to do with its requirement that Berkshire mark its investment portfolio to current “fair” market values on its balance sheet and therefore book corresponding gains or losses on its income statement depending on whether those market values went up or down. This creates massive volatility, with Berkshire reporting a $23B loss in 2022 compared to $96B of profit in 2023, with little to no impact on the company’s operating cash flow since Buffett has no interest in selling his investments.

For Buffett, these numbers are “worse-than-useless,” and I don’t disagree. So then the question becomes what numbers are useful?

In that same letter, Buffett says that his target audience for his letter is his sister Bertie who is “very sensible” and “understands many accounting terms, but…is not ready for a CPA exam.” And he posits that what she would find useful, at least as a starting point, is operating earnings, which is a measure of business performance that throws out those mark-to-market gains and losses and other line items such as interest expense in order to report on how much money Berkshire’s companies are making by opening for business every day.

And while those earnings are more consistent and do a better job of giving someone like Bertie a sense of Berkshire’s viability, I would posit that they are also not that useful in evaluating Berkshire as an enterprise. After all, making successful investments is a huge part of Berkshire’s value proposition, and those investments account for almost half of the company’s $800B balance sheet. To not bother reporting on how they’re doing seems like an oversight and also how they’re doing seems like something Bertie would want to know! Further, Berkshire doesn’t look as good as an investment through the operating earnings lens (trading at 25 times) as it does when one takes the entire balance sheet into account (trading at 1.5 times book value).

The point is numbers, no matter how you slice and dice them, will always be deceiving. Even my hallowed beer money metric falls down when it comes to evaluating Berkshire – after all of its investments, capital expenditures, and payments on debt, the company added just (relatively speaking) $2.2B of cash to its balance sheet in 2023 (sorry, Bertie). But of course much of that reinvestment was discretionary, i.e., it could have been beer money instead. And given Berkshire’s investing track record, foregoing beer money now should mean more beer money in the future.

So where does that leave us? Well, if numbers can always be deceiving, then the only thing we can do is to try to work with people who won’t use them that way. Because what’s the point of beer money if you don’t want to have a beer with the people you earned it with? Cheers.

P.S. Danny didn’t get a glass.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

BS Earnings and Unconscious Reinvestment

I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised that more than a few people were interested in what Permanent Equity does with its money. After all, it’s one thing to brag about bullshit earnings (shoutout Charlie Munger) and another to be able to buy beer. And what people wanted to know most is how much cash our companies actually generate?

The answer to question one is a moving target because we live and work in the real world where nothing is ever reliably stable let alone up and to the right, but we have aspirations that our portfolio companies generate in cash at least 90% of what they claim to have earned in a given month. Some call this free cash flow conversion, but we refer to it as earnings quality, and if any of our companies come up short of that 90% target in a given month, and we have spreadsheets to measure it, we want to understand why.

That’s because it’s in understanding why a business did or did not have good earnings quality that a lot of aha moments happen, in particular with regards to operating a small business. For example, one idea I’ve come to believe is that reinvestment, which is what is happening if earnings are not showing up on the balance sheet in cash, takes two forms: (1) conscious and (2) unconscious.

Conscious reinvestment is great. It’s the deliberate deciding on and then spending against a strategic priority whose risk/reward profile is both known and attractive. And if we have a business that’s not generating much cash because it’s consciously reinvesting, that’s, again, great. We’re using pretax dollars to drive growth and the cash should show up later.

What’s insidious, however, is unconscious reinvestment. This is what I’ve started calling it when a bunch of invoices get paid early because someone is on vacation next week, we decide to buy instead of lease some new equipment to get a price break, we hired someone a little earlier than plan because it was a serendipitous fit, and the back office got busy and missed a billing cycle or didn’t make any phone calls to inquire about past due receivables.

Because each one of those decisions on their own isn’t the end of the world, but if they all happen in the same month, and they can because different individuals are the decision-makers and they may not be coordinating, poof, our earnings quality may have just got cut in half without anyone realizing it. And God forbid if you fill that gap with a draw on a line of credit without figuring out why the gap exists in the first place.

That’s why having a goal of banking at least 90% of its earnings is effective. It doesn’t mean it will happen every month, but if it doesn’t, and you’re not consciously reinvesting, at least the shortfall will shine a light on your unconscious reinvestment and therefore on what process improvements need to be implemented in order to nuke it.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Seven Reasons to Sell

Our founder and CEO Brent is getting set to update his 2018 book The Messy Marketplace later this year. Perhaps exciting news on its own, the point here is that in advance of that, we’ve all been re-reading what was said way back when to help figure out what’s changed (e.g., interest rates) and what’s been learned since then (e.g., how might a buyer and seller meet in the middle around a massive business disruption like a pandemic) to make sure any second edition is a step up from the first.

And while there is quite a bit of change and learning that should add some nuance to the book, what’s been most interesting to me in reviewing the project is what hasn’t changed. The reason that’s so is because a lot has changed since 2018, so if something fundamentally hasn’t, it might be the case that that thing is a constant. And since constants are rare in this world, that makes it potentially notable. For example, Brent wrote in 2018 about the seven root motivations for transitioning a company to new ownership. They are:

1. Personality/skills: We’re growing faster than I know how to handle.

2. Exhaustion: I’m burnt out and my heart just isn’t in it anymore.

3. Freedom: I’m ready to wake up in the morning and think about something else.

4. Health: If my doctor had it her way, I’d already be retired.

5. Obligations: I promised my wife at age 65 we could start doing all the things we never had time to do before.

6. Risk: I can’t manage through another major business disruptions and need to take some chips off the table.

7. Legacy: I want to make sure that the team I’ve built can continue forward with good support.

Money, of course, is not on this list because as Brent pointed out back then, due to taxes and the power of compounding gains, a business owner will “almost always do better financially…by not selling.”

But back to the seven motivations…

I spent considerable time racking my brain to come up with another one and couldn’t. So if you have a business, or really any significant obligation or responsibility, and one of those seven things is true of you, now might be the time to consider how to transition out. It may cost you, but could also well be worth it.

Have a great weekend, and look for the updated Messy Marketplace in the fall.

— Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What’s Enough Waterproofing?

Apparently I’m not the only one in the world struggling with the relationship between inputs and outcomes because there was a lot of reaction to the idea of slack time as presented in “Can Main Street Innovate?” and then the next day to being whole-ass or half- when it comes to effort.

Andrew, for example, pointed out that you might not know what was a good use of time and effort until well after the fact, and so any work building domain expertise might end up proving to be rewarding. Matt, on the other hand, pointed me to Parkinson’s Law, which is the idea that the scope of a job to be done will expand to fill the time allotted to complete it, but further noted that Toyota demands a 0% defect rate in manufacturing because if its goal was something more realistic (like 0.1%) then the actual result would likely be something unacceptable (like 0.2%).

This was all rolling around in my head when we met with some folks who do waterproofing for a living. In talking about their business, they noted that they have three types of customers:

Long-term owners who want and will pay up for waterproofing that will last for decades.

Short-term owners who want and will only pay for sufficient waterproofing to pass inspection at sale.

General contractors that only care if the waterproofing will last through warranty period on their work.

And so these three types of customers make very different choices about what designs and materials to employ, some of which will work longer and perform better than others. In other words, when you see an example of work after the fact where someone ostensibly did a “bad job,” it may be the case that it wasn’t a bad job at all, but was exactly the job the customer wanted done given his or her goals with regards to cost, durability, and longevity.

The reason this is relevant here is because a fair question to ask is if customers (2) and (3) are half-assing it. Further, if most of us make choices most of the time that optimize for our desired outcome rather than the objectively best outcome, does this mean that we all spend most of our time doing things that are not our best? And if that’s true, is that depressing?

I think the answer to that question is yes, but also that it’s not as depressing an answer as it might seem on its face.

See, Brent, Mark, and I then hit on this line of thinking again in a separate conversation about what a common north star for our portfolio companies might be. “What about high-single-digit organic cash flow growth?,” I suggested.

“Maybe,” Brent and Mark responded.

And the reason that’s a maybe is because depending on the circumstances, high-single-digit organic cash flow growth might be a perfect goal for one company but a wholly inappropriate goal for another even if high-single-digit organic cash flow growth might be better than the alternative. Instead, we want to target a goal on a case-by-case basis that puts us at that moment in time on the spot we want to be on the efficient frontier between risk and reward.

So given all of the choices, the question is “What’s enough waterproofing?” And while I want to say, do it right, I think the answer is actually “It depends.” Because doing something the best you can is both time consuming and expensive and therefore might not be right or optimal. But also beware the Toyota problem, which is that if you don’t at least try to do the best, you might end up much worse off.

Or as the waterproofers pointed out, leaks are inevitable. It’s only a matter of when and how big.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

More is Better than Less

A cynical approach to negotiating is to always ask for more. After all (and this was actually said to me verbatim once), more is better than less and you don’t get 100% of the things you don’t ask for. Further, if you can do this from a position of strength, when it comes to isolated negotiations, you are going to win more than you lose.

What this strategy ignores, however, is that the more often one employs it, the more likely the world becomes to not want to negotiate with you. And since life is in some sense a never-ending series of negotiations, having the world not want to negotiate with you means cutting off the chance at open-endedness, which is an expensive prospect given that the theoretical value of open-endedness is infinite. In other words, being an aggressive and self-interested negotiator doesn’t mean you will lose negotiations, but rather that over time you will have fewer chances to negotiate.

One thing that I’ve observed to be true is that most of us overvalue near-term certainty and undervalue long-term optionality. Consider, for example, the hypothetical case of a key vendor that leverages its in-stock position on raw materials important to a small business during a supply chain disruption caused by a global pandemic to significantly increase the price of that material to that small business. While the vendor is likely to get what it's asking for, it will come at the cost of the small business reducing its reliance on that vendor and willingness to build capabilities around said partnership. And so we should all do the math in thinking about that trade-off and decide if we as people and organizations want a bigger piece of a smaller pie or its opposite.

None of this is to say that people or partners shouldn’t be compensated fairly, but rather to observe that if you present value any growing stream of cash flows, the majority of the total value is typically concentrated in the terminal value, i.e., the value that is created beyond the forecast period. Think about that for a moment: We have no visibility into how or why most value will be created.

Now, I’ll admit that’s maybe overstating the practical implication of an abstract mathematical formula, but when it comes to thinking about how to approach negotiation, I don’t think it’s too far off. After all, more truly is better than less, and the variable that matters most to generating more is not performance during any single unit of measurement, but the duration of your measurement period.

Said differently, if your goal is to negotiate for the most, then figure out what will get you more time and opportunity beyond the forecast period. And if you think about it that way, rarely will the answer be more dollars now.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Tell Me I Did a Good Job

Most people know by now that one way I quality control these missives is by sending them out internally at Permanent Equity for feedback before they are even considered for consumption by the outside world. This is why the ones that are “not my best” never see the light of day and so therefore you think (maybe? I hope?) that I am clever more consistently than I really am.

And I also hope that I do a decent job of communicating to the people at Permanent Equity how much I value their feedback, good, bad, or indifferent. Yet even Brent, after a string of pretty decent ones, replied “I’ll stop replying to all of these with ‘good job’...but…good job.’”

And I said, because it’s true, “Keep replying! It’s nice to start my morning with an affirmation.”

I don’t relay this story to toot my own horn, but rather because I think it’s illustrative of the fact that no one puts something out into the world without wanting a genuine response. Yet for some reason many of us are programmed to think that we might be bothering or burdening someone by responding.

For example, I sent an email recently to our investors to gauge interest in whether or not they would attend a Partner Summit here in Columbia, Missouri. I got a number of responses and duly noted in a spreadsheet who might and might not attend. A few days into receiving those responses Brent, who was cc’d on some of them, said, “Hey, are you responding to these?”

And I said, “No, I didn’t want to clog up people’s inboxes. I was going to respond to everyone when we had a decision on whether or not to move forward with the Summit.” As soon as I said it, I knew what I had said was stupid. Why wouldn’t I respond and thank them for their response and say we would be excited to see them? Not only is it true, but in all cases I could and can think of, recognition is better than a vacuum.

Another thing this got me thinking about is the relationship in a relationship between duration and contact frequency. My experience is that when someone makes a new friend, there’s a surge of activity that decays over time even though it seems like the opposite should be true. And I’ve experienced that with this daily. Most of the responses I get back (aside from Brent, who writes me back a lot) are from people I’ve never heard from before, but my favorite responses are usually from people who have already written back a few times (note that you have to write once in order to write twice).

Again, I can’t put my finger on why that is, but if you have insight, I’m all ears. What I do think is true, however, is that nobody doesn’t want to hear from you provided that what you are sending is both genuine and thoughtful (stay away, spammers). At the risk of repeating myself, it turns out we’re social creatures.

— Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What’s Your Secret Formula?

Back when I explained how we set out to brew the world’s best cup of coffee, I shared three paradigms that might help one achieve success at anything:

You’re only as strong as your weakest link, i.e., the best you can do is your worst input.

The whole is greater than the sum of its parts, i.e., your inputs are all better together.

Go big or go home, i.e., your best input is your biggest driver.

Soon after, I heard back from Paul who said, “That’s great and all, but how do you know what your best and worst inputs are? There are only so many in your coffee example, but in a business there could be tens or hundreds.” And while it’s true that revealing how to brew the world’s best cup of coffee was a deliberately simple example, that doesn’t mean that more complicated use cases are lost causes.

Way back when, I shared Permanent Equity’s secret formula, a legitimate mathematical equation that makes clear the relationship between the variables that contribute to our success as a private equity investment firm:

Clearly, if Permanent Equity is succeeding, it’s because we have capital and deal flow, have done a good job analyzing businesses and negotiating terms, and have added value post-close. And if we want to do even better, we can look at this equation and decide where we want to double down.

If, on the other hand, there comes a time when Permanent Equity is not performing well, it will likely be because we’ve fallen down in one or more of these areas. As for which it might be, if we’re tracking what we should, that should be pretty clear in the numbers. And once we know that, we can decide if we want to try to fix what’s not working, double down on what is, or rejigger the equation. For example, if we’re not adding value post-close, well, that problem not only won’t get solved by having more deal flow, but probably gets made worse. Raising more capital, however, might solve deal flow challenges because when people know you have access to capital, they tend to bring you opportunities to invest it.

So what I said to Paul was if you’re trying to achieve something and you’re not sure why it is or isn’t being achieved as you would like, write it down as a secret formula and then analyze each contributing variable independently. As you do so, you may find that each can be further broken down into sub-variables – keep doing that until what you are trying to achieve has been set equal to a finite number of controllable inputs.

Because when that’s done, you should be able to see what matters, identify what is and isn’t performing as expected, and then start the hard work of deciding what to do about it.

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

If You Get the Chance to Ask…

One thing I’ve learned is that when you meet someone new, particularly if it’s a business introduction, it may end up being the only time you ever talk to that person, so if there is something interesting about them, you should ask about it, because you may never get another chance. And this is how I ended up derailing a conversation between Emily and I and an investment banker when, in the course of telling us about his background, he said that he had worked in the accounting department at Enron from 1996 to 2001.

You know, 2001? When that entire company collapsed amid a massive accounting scandal.

“You worked at Enron from 1996 to 2001?” I asked.

“Yes,” he confirmed.

“What was that like?” I got out before Emily kicked me under the table.

“Uh, stressful,” he replied.

“Could you tell? Did you know?”

He said, “No, not really, I wasn’t in the top levels, but I did start to think something was odd when I saw what the company was valuing its Venezuelan investments at. I mean, Chavez had just taken power and it didn’t seem like they could be worth much. But that’s why I got subpoenaed by the Department of Justice?

“You got subpoenaed by the Department of Justice!?” I spit out.

At this point, Emily was not amused. Breakfast was close to over and we knew nothing more about the deal he was there to tell us about. But this was too good.

“So what was that like?” I continued before she could redirect.

“Uh, stressful,” he repeated. “I went in there without a lawyer thinking it would be a pretty straightforward conversation since I didn’t know very much.”

“Was it?”

“No.”

“Hmm. What’d you learn?”

“Well,” he thought it over, clearly reliving the experience in his mind. “I learned to never again respond to a Department of Justice subpoena without a lawyer.”

And that, I thought, was a pretty good learning to get and well worth the time spent getting it. That said, we also didn’t get the deal.

Have a great weekend.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Transparency? Yes!

At the risk of oversimplifying, owners of small businesses don’t often share financial results with their employees because they don’t want them to either (1) know how good it is or (2) know how bad it is. And that makes sense. It sucks to be resented because you’re rich just as much as being pitied because you’re poor.

But I will advocate for transparency with this story about our COO Mark…

Back in a previous life Mark took over a struggling business unit at a big company. This was a business line that should have had 40%+ net margins, but was instead trying to avoid tripping a bank covenant. Fast-forward a few years and the team had 10x’d the bottom line. Was it rocket science? Not as he tells it. Rather, the things he focused on were surprisingly straightforward:

1) Transparency: We started openly sharing our numbers and our challenges with the entire company.

2) Accountability: We made sure each key part of the business had a capable leader and they knew what their goals were.

3) Unity: That leadership team met regularly to talk about their challenges and solve them together.

In other words, he changed very little about the business other than how honest and open it was between and among the people working in it. But why did that work?

One explanation could be dumb luck. Maybe the industry took a turn for the better and whatever Mark and his team did would have been successful no matter what. But I think that underestimates what people can accomplish when they are armed with information.

Because even the rocket scientists among us can’t solve problems or optimize opportunities if they don’t know that those problems and opportunities exist.

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Time to Lawyer Up

I’m always on the lookout for things that are uncorrelated and countercyclical, so you might not be surprised to learn that with the economy potentially slowing I told our chief legal officer (and resident coffee aficionado) Taylor that it’s time to start suing people. I’m kidding, of course (we only sue on the merits), but what is true is that it is a strategy for others. Simply put, when the economy goes down, litigation goes up.

This makes sense. Economic downturns can cause companies to terminate employees and break contracts, which are events that leave counterparties aggrieved, but they also tend to make people poorer and crankier, which are anecdotally the catalysts behind most lawsuits. In fact, we were talking to a structural engineer the other day who had built a commercial construction consulting business with remarkably smooth revenue growth that didn’t seem to ebb and flow with the commercial construction industry. The secret, he revealed, is that in addition to advising contractors on how to build things, he had gotten certified to serve as an expert witness in court to testify at cases of construction projects gone wrong. “When there is money to be made,” he said, “everybody works hard to make it. But when the money dries up, everyone thinks they should have made more.”

What’s interesting about all of these cases, however, is that very few of them (1% to 5%, depending on your source) ever go to trial. That’s because, to quote the aforementioned pithy structural engineer, “everyone knows the last place you’ll find justice is in court.”

If you’re like me (i.e., competitive and never wrong), that’s really frustrating because it means that people who are in the wrong are winning paydays or not being held accountable for their wrongful actions. In fact, I’m pretty sure that the most common attorney/client conversation goes something like this:

Client: What do you think I should do?

Attorney: Settle.

Client: ARGH!

As for why this is (leaving aside the simplest explanation that attorneys lack follow through), I asked Taylor and he attributed it to certainty and agency.

On the certainty side, since you never know what a judge or jury might do, your range of outcomes is unknown and unknowable, whereas one can negotiate a settlement agreement down to the last letter. While this guarantees every lawsuit against you will cost you something (certainty is expensive!), it means that you can at least make sure you get something for your money.

As for agency, a reality is that many civil lawsuits get passed off to insurance companies who (1) aren’t personally competitive; (2) are regulated and have no appetite for open-ended liabilities; and (3) can spread incurred settlement costs across their entire base of customers in the form of higher premiums. The tragedy of the commons strikes again.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Crazy and/or Well-Moisturized

Like most Americans, our office spent an inordinate amount of time after the Super Bowl talking about the ads (and also relishing in our local area sports team’s third championship in five years, but I don’t want to rub that in because we have prospective deals in both Baltimore and the Bay Area). And while we enjoyed The DunKings ad a lot, the consensus favorite was Michael Cera revealing that human skin is his passion. And it was in the course of reaching that conclusion via the Socratic method that Brent noticed a small white tub on Holly’s (shoutout Gen Z and thanks for your help writing this one) desk and said, “Wait, is that CeraVe?”

And as soon as he said it we could all see Holly winding up and then maybe Brent regretting that he asked.

“Yes!” she said. “I carry a travel-sized CeraVe Daily Moisturizing Lotion with me everywhere I go. I keep a 12 oz. tub of CeraVe Moisturizing Cream at my desk, a 16 oz. pump top tub of CeraVe Moisturizing Cream on my nightstand, and a 19 oz. tub of CeraVe Moisturizing Cream in the waiting just in case I run out. Some might call this crazy; I call it being well-moisturized. But you know what the problem is, Brent?”

Brent looked at me for support, but there was no way I was intervening.

“The problem, Brent, is that a few years ago I splurged and purchased the 16 oz. pump top CeraVe Moisturizing Cream. Each time the tub ran out of cream, I just purchased a non-pump top replacement tub, and changed out the lids. Until December 8, 2023, when I didn’t want to brave the holiday rush at Target and opted to order the 19 oz. tub from Amazon for $16.02. While I thought I was getting more bang for my buck, the 16 oz. pump top lid doesn’t fit the 19 oz. container. Can you believe that, Brent?”

Brent again looked at me, but I averted my gaze.

“So now there I am, Brent, physically scooping the cream out of the 19 oz. tub and into the 16 oz. container like I’m Pooh Bear with a honey pot just so I can use my pump top. Does that seem right, Brent?”

“How much more is the 19 oz. container with a pump top?” Brent asked.

“Double the price,” responded Holly.

“In dollars?” Brent inquired.

“16!” said an outraged Holly.

“Can I give you $16?” asked Brent, hoping beyond hope that Holly would say yes.

“It’s not the money, it’s the principle, Brent. Both you and Michael Cera should understand that. The tub lids should all be the same diameter so I can continue using my years old pump top on new tubs of this fabulous moisturizing cream.”

And it ended there because fortunately Jenny had catered in barbecue for the office that day so we all had a pulled pork lunch to get to, but it just goes to show that even innocent questions can prompt unlikely diatribes.

As for why I am telling this story here, I (1) needed to acknowledge that the Chiefs won the Super Bowl (again, sorry Baltimore and the Bay Area); (2) thought it was funny; and (3) wanted to revisit the risk/reward calculus of businesses making life harder on their customers in pursuit of near-term profits. This is also Amazon continuing to degrade the value proposition of Prime and food companies that shrink portions to surreptitiously maintain margins amid rising costs.

Businesses, of course, are frequently run by the numbers, but it’s one thing for them to be an objective and another to be a byproduct. As for whether or not juicing profits by charging more for no-longer-interchangeable pump tops is what’s behind CeraVe’s packaging geometry, I have no idea. But I do think Holly, whether crazy and/or well-moisturized, has a point.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Have Hard Conversations

One of the things that’s true about our line of work is that we have a lot of stakeholders. As a result, we have a lot of hard conversations. That’s because stakeholders are people and people, as Brent likes to say (and we’ve all adopted the saying), are messy.

It’s for that reason that the piece of content on our website that I refer back to the most is our Tactical Guide to Tough Conversations. And I refer back to it before each time I think I am going to have a hard conversation (there is, by the way, no difference between a tough or hard conversation, but the person who titled that piece liked alliteration and went against my recommendation to call it The Hitchhiker's Guide to Hard Conversations) because hard conversations are by definition hard and you’re probably only going to get one shot at having one and having it go right, so you need to make sure you’ve thought it all the way through and are prepared for whatever direction it might go. In other words, read The Guide.

Further, another thing that’s true about hard conversations is that if you’re the one initiating one, the person you’re having it with may not have known ahead of time that a hard conversation was on the horizon and therefore may not be at all prepared for it. This is important to recognize because if it’s true, that person is likely to react emotionally, which puts the onus doubly back on you as the initiator to make sure that the conversation is trafficking in facts in pursuit of an achievable and desirable outcome.

How can you do that? Here’s what our Guide says:

Know why you’re having the conversation and what the achievable and desired outcome is.

Recognize going in that one conversation won’t solve everything, so appreciate that this conversation is likely the beginning (and not the end) of a larger conversation.

Prepare and practice for the conversation out loud.

Be specific and direct with examples.

If the conversation is escalating or getting emotional, bring it back to its purpose and achievable and desired outcome.

The reason these principles work is that they solve for the developments that tend to make hard conversations go off the rails. Namely:

Asking for something that’s not achievable.

Expecting resolution and becoming frustrated when it can’t be reached.

Saying something off the cuff that’s stupid.

Not being able to support a point of view with evidence.

Open-endedness; when one thing becomes about everything.

The other key to a hard conversation is ending it, and the best way to do that is by identifying an agreed upon next step. After all, the only way forward is progress, so be satisfied if, after what’s probably been an emotionally draining experience for both parties, you’re able to agree that you’ve made it.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

How to Build a Portfolio

Our CEO Brent and I were talking the other day, as we regularly do, about investing. And more specifically about portfolio construction as in “what type of opportunity might we want to invest in next.” Because in a world like ours, where there aren’t thousands of opportunities listed and traded daily on efficient public markets, it helps to have an idea of what you’re looking for so you don’t miss it when you see it. That’s the importance of preparation when your chances to act are finite and intermittent.

As we talked that through, though, it also dawned on us that neither of us are classically trained in investing. And so while we now are well aware of things like the Kelly criterion and correlation coefficients for sizing and measuring bets, we had practical experience of the implications of those things before we had the specific technical knowledge.

An implication of that is that there is healthy tension between the qualitative and the quantitative in the way we think about building a portfolio of investments, which you could probably guess just by eyeballing, without knowing the position sizes, valuation multiples, or financial condition of any of them, Permanent Equity’s portfolio.

So what’s the method to the madness?

In thinking through how we have built our portfolio, five tenets emerged, learned over time, that I thought might be helpful to others who are trying to build a portfolio of anything, with portfolio here being defined as individual things that need to cohere in order to do one thing successfully.

Know what you’re trying to accomplish.

Don’t risk more than you can afford to lose.

Diversify, but not too much.

Only take risks you’re compensated for taking.

Everything is more correlated than you think.

The plan is to explain each of these in significantly greater depth (do I hear “white paper”?) at some point in the future, but for now, have a great weekend.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

This is Urgent

Responding to the idea that the point is constraints, Stephen wrote back, “It brings up an interesting question. How can we create that sense of urgency…when it’s not naturally there?”

To which I replied, “Great question. I don’t think we spend much time thinking about how to make life harder for people, but maybe we should?”

And as owners and operators of businesses, I think that’s mostly true. In my career, I’ve been fortunate to work for organizations that treated people well with much of what I’ve heard from managers being something along the lines of “What do you need?” or “How can I help?” This is also a tactic I’ve tried to employ as I’ve been entrusted to lead teams.

Yet as I reflected on that, it also became apparent to me that while at those organizations that treated people well, some of the best work the people in those places did was done when deteriorating exogenous economic conditions forced them to really dial-in. So an open question is: Would an organization achieve better performance if everything were more difficult and stressful more often if not all the time?

As I thought about that, I realized there are times when we do make things deliberately harder on others. One obvious example is sports practices. During soccer scrimmages, we often limit the girls to one or two touches. When I played baseball in high school, practice at-bats would start with two strikes. And in basketball the coach might give you only five seconds to shoot out of an inbounds play. The goal of these scenarios is to force a practitioner to operate under pressure so that person not only learns to deal with that pressure, but also so that the game would feel easier when those deliberately applied hardships were removed.

A key difference between sports and business, however, is that sports have clearly delineated times to focus on process (practices and training sessions) versus outcomes (competitive matches and games), whereas in business the line is much more blurred. Sure, most businesses offer some form of “training,” but it’s typically done on the job. Further, while athletes spend significantly more time practicing than playing, employees in the U.S. are lucky to get one hour per week of “practice.”

But what would practice at work look like anyway? There isn’t enough time in the day and business, unlike sports, has no clear rules of engagement. A worker might practice a process to perfection only to have it be deemed irrelevant the next day.

Another risk of amping up the pressure on employees is burnout. In other words, how much sub-optimal performance is tolerable in order to keep turnover low? Because a lot of turnover is likely to lead to significantly lower performance than what you’d get from a good, long-tenured personal who’s dialed-in, but just not really dialed-in. Further, it may be the case that the ability to really dial-in when necessary is enabled by not having to be really dialed-in all the time.

And maybe that’s the answer. That value creation is not linear and therefore most of our time should be spent creating conditions that enable high performance so we can achieve it in the moments it’s most necessary.

-Tim

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Work Changes You

Permanent Equity was fortunate to have Steve Cockram zoom into one of our recent Lunch ‘n Learns to talk about his 5 Voices framework and new book The Communication Code. As an aside, and lest you think we are inhospitable, he was supposed to be here in-person, but the Lunch ‘n Learn ended up being planned for one of those weeks in winter when Columbia, Missouri, briefly turned into the East Antarctic Plateau (variance!). I digress…

I wrote about Steve previously in this space in the context of using words wisely, but Steve’s expertise goes so much deeper than that. So read the books. Both the Voices and the Codes will help you become a better communicator in both your professional and personal lives.

This, though, is about something slightly different. See, Steve and I have gotten to know each other a little bit and during the course of his talk, I asked a question. In the course of his answer, because he knew me a little bit, he referred to me as a Pioneer/Creative, which was interesting to me because I had recently taken the 5 Voices assessment and measured out as a Guardian. So as a follow-up question, and because all Lunch ‘n Learns should be about me, I asked how he had pegged me as a Pioneer/Creative and if I was that, why would I have tested as a Guardian?

His answer was that he thought I had told him previously that I was a Myers Briggs INTJ, which would correlate with being a Pioneer/Creative. When I clarified I was an ENTJ, he said that that would mostly make me a Pioneer/Guardian. But as for why I was testing as a Guardian, well, that was a different story.

The reason that might be, Steve said, is because in my previous role as CFO and now as CIO, I had a lot of responsibility for making data-driven decisions, watching the numbers, and doing due diligence. As a result, I likely changed as a person because of my onus of work.

That blew my mind. It sounded ridiculous, but was also probably true.

The reason this is so is because it’s not just nature that determines who we are and become, but also nurture, i.e., how we modulate ourselves based on our experiences and choice, i.e., what we choose to emphasize based on feedback we receive and perceive. In other words, I may have changed my persona based on what was expected of me, what voids I felt I needed to fill, and what I thought might earn me praise or blame.

As I wrestled with that, I realized that if what someone does for work changes him or her as a person, then it’s critical that ultimately what that someone does makes him or her (1) happy and (2) a better person.

Of course, it’s not realistic to think that can be the case all of the time. But if you find yourself in a situation where it isn’t, you might spend time thinking and talking with others about what you can do and what it might look like to work towards a situation where it is.

-Tim